11.16. Real-time SQP Solver: Robotic Arm Manipulator (MATLAB & Python)¶

In this example we illustrate the use of the real-time Sequential Quadratic Programming (SQP) solver and how to generate and call the dynamics used in the formulation of the optimization problem directly in MATLAB/Python. In particular, we use a robotic arm manipulator described by a set of ordinary differential equations (ODEs):

where \(\theta_1, \theta_2\) are joint angles modelling the manipulator configuration, \(u_1, u_2\) are the rates (inputs) of the torques \(\tau_1, \tau_2\) applied to the joints and

The coefficients \(\alpha_1, \alpha_2, \alpha_3, \alpha_4, \alpha_5\) and \(\beta_1, \beta_2, \beta_3, \beta_4\) depend on the inertia and mass of the robot arm components. Their expressions can be found in [SicSci09]. The optimal control problem is formalized from the state \(x\) defined by

and the input \(u\) defined as

The control objective is to make the first joint angle \(\theta_1\) follow a reference of \(1.2\,\mathrm{rad}\) from \(0\) to \(10\,\mathrm{s}\) and \(-1.2\,\mathrm{rad}\) from \(10\) to \(20\,\mathrm{s}\). Similarly, the second joint angle \(\theta_2\) should follow a reference of \(-1.2\,\mathrm{rad}\) from \(0\) to \(10\,\mathrm{s}\) and \(1.2\,\mathrm{rad}\) from \(10\) to \(20\,\mathrm{s}\). The stage variable \(z\) is defined by stacking the input and differential state variables:

You can download the MATLAB code of this example to try it out for yourself by

clicking here

along with the dynamics here.

The Python code is available here

along with the dynamics here.

11.16.1. Defining the MPC problem¶

11.16.1.1. Tracking objective¶

Our goal is to minimize the distance of the joint angles to the reference, which can be translated in the following stage cost function:

where \(p\) is a run-time parameter taking value \(1\) from \(0\) to \(10\,\mathrm{s}\) and \(-1\) from \(10\) to \(20\,\mathrm{s}\).

The stage cost function is coded in MATLAB as the least-squares vector:

model.LSobjective = @(z,p)[sqrt(1000) * (z(3)-p(1)*1.2); ...

sqrt(0.1) * z(4); ...

sqrt(1000) * (z(5)+p(1)*1.2); ...

sqrt(0.1) * z(6); ...

sqrt(0.01) * z(7); ...

sqrt(0.01) * z(8); ...

sqrt(0.01) * z(1); ...

sqrt(0.01) * z(2)];

model.LSobjective = lambda z, p: casadi.vertcat(np.sqrt(1000) * (z[2] - p[0]*1.2),

np.sqrt(0.1) * (z[3]),

np.sqrt(1000) * (z[4] + p[0]*1.2),

np.sqrt(0.1) * z[5],

np.sqrt(0.01) * z[6],

np.sqrt(0.01) * z[7],

np.sqrt(0.01) * z[0],

np.sqrt(0.01) * z[1])

In the MATLAB example, this is needed to compute a Gauss-Newton approximation from the Jacobian of the least-squares vector. In the Python example, where Gauss-Newton approximations are not yet available, we use the objective field to supply the target function.

11.16.1.2. State and input constraints¶

The following constraints are imposed on the torques and torque rates:

This corresponds to the code below.

% upper/lower variable bounds lb <= x <= ub

model.lb = [ -200, -200, -pi, -100, -pi, -100, -100, -100 ];

model.ub = [ 200, 200, pi, 100, pi, 100, 70, 70 ];

# Upper/lower variable bounds lb <= x <= ub

# Inputs | States

# dtau1 dtau2 theta1 dtheta1 theta2 dtheta2 tau1 tau2

model.lb = np.array([ -200, -200, -np.pi, -100, -np.pi, -100, -100, -100])

model.ub = np.array([ 200, 200, np.pi, 100, np.pi, 100, 70, 70])

11.16.1.3. Initial condition and horizon length¶

The prediction horizon is set to \(21\) and the following initial condition is set

model.xinit = [-0.4 0 0.4 0 0 0 ]';

model.xinitidx = 3:8;

xinit = np.array([-0.4, 0, 0.4, 0, 0, 0])

model.xinitidx = range(2, 8)

11.16.2. Generating a real-time SQP solver¶

We have now populated model with the necessary fields to generate an SQP solver, which requires settings a few options, as follows:

%% Define solver options

codeoptions = getOptions('RobotArmSolver');

codeoptions.maxit = 200; % Maximum number of iterations of inner QP solver

codeoptions.printlevel = 0; % Use printlevel = 2 to print progress (but not for timings)

codeoptions.optlevel = 3;

codeoptions.nlp.integrator.Ts = integrator_stepsize;

codeoptions.nlp.integrator.nodes = 5;

codeoptions.nlp.integrator.type = 'ERK4';

codeoptions.nlp.ad_tool = 'casadi';

% Options for SQP solver

codeoptions.solvemethod = 'SQP_NLP';

codeoptions.nlp.hessian_approximation = 'gauss-newton'; % Gauss-Newton hessian approximation of nonlinear least-squares objective

codeoptions.MEXinterface.dynamics = 1; % Generate a MEX entrypoint for the nonlinear dynamics of the robot

# Define solver options

codeoptions = forcespro.CodeOptions()

codeoptions.maxit = 200 # Maximum number of iterations

codeoptions.printlevel = 0 # Use printlevel = 2 to print progress (but not for timings)

codeoptions.optlevel = 3 # 0 no optimization, 1 optimize for size, 2 optimize for speed, 3 optimize for size & speed

codeoptions.nlp.integrator.Ts = integrator_stepsize

codeoptions.nlp.integrator.nodes = 5

codeoptions.nlp.integrator.type = 'ERK4'

codeoptions.solvemethod = 'SQP_NLP'

codeoptions.sqp_nlp.rti = 1

codeoptions.sqp_nlp.maxSQPit = 1

codeoptions.nlp.hessian_approximation = 'gauss-newton'

# Generate FORCESPRO solver

solver = model.generate_solver(codeoptions)

The number of solved QPs in every iteration is set via sqp_nlp.maxSQPit. It is important to note that disabling the line search in the SQP algorithm does not guarantee global convergence and hence may result in less robust performance, but produces much faster solve times.

Turning off the line search via sqp_nlp.use_line_search is only allowed when the Gauss-Newton approximation is on.

11.16.3. Calling the generated SQP solver¶

Once all parameters have been populated, the MEX interface of the solver can be used to invoke it from MATLAB, or the Python Solver class can be used to use it from within Python:

% Set primal initial guess

x0i = model.lb+(model.ub-model.lb)/2;

x0 = repmat(x0i',model.N,1);

problem.x0 = x0;

% Set reference as run-time parameter

problem.all_parameters = ones(model.N,1);

% Set initial condition

problem.xinit = X(:,i);

% Call SQP solver

[output, exitflag, info] = RobotArmSolver(problem);

# Set solver parameters

x0i = (model.ub + model.lb) / 2

x0 = np.tile(x0i, (1, model.N))

problem = {"x0": x0, # Primal initial guess to start solver from

"xinit": xinit, # Initial condition

"all_parameters": np.ones((model.N, 1))} # Reference as a real-time parameter

# Call SQP solver

output, exitflag, info = solver.solve(problem)

The RobotArmSolver is expected to return an exitflag equal to \(1\), which corresponds to a successful solver. However, note that the QP could become infeasible in some cases. In this case, one should expect an exitflag of \(-8\).

11.16.4. Calling the dynamics used in the model directly in MATLAB/Python¶

The MEX interface for the dynamics used in the formulation of the optimization problem can also be called directly in MATLAB and in Python, the Solver class has a method which can compute the dynamics along with its derivative (see section Calling the nonlinear functions from MATLAB or Python). This is convenient for debugging a solver formulation or simulating the system dynamics. This can be done as follows:

% Set data at first stage

z = problem.x0(1:model.nvar);

p = problem.all_parameters(1:model.npar);

[c, jacc] = RobotArmSolver_dynamics(z, p);

# Set data at first stage

z = problem['x0'][0:model.nvar]

p = problem['all_parameters'][0:model.npar]

c, jacc = solver.dynamics(z,p)

This stores the integrated stage in c and its jacobian with respect to z in jacc.

11.16.5. Results¶

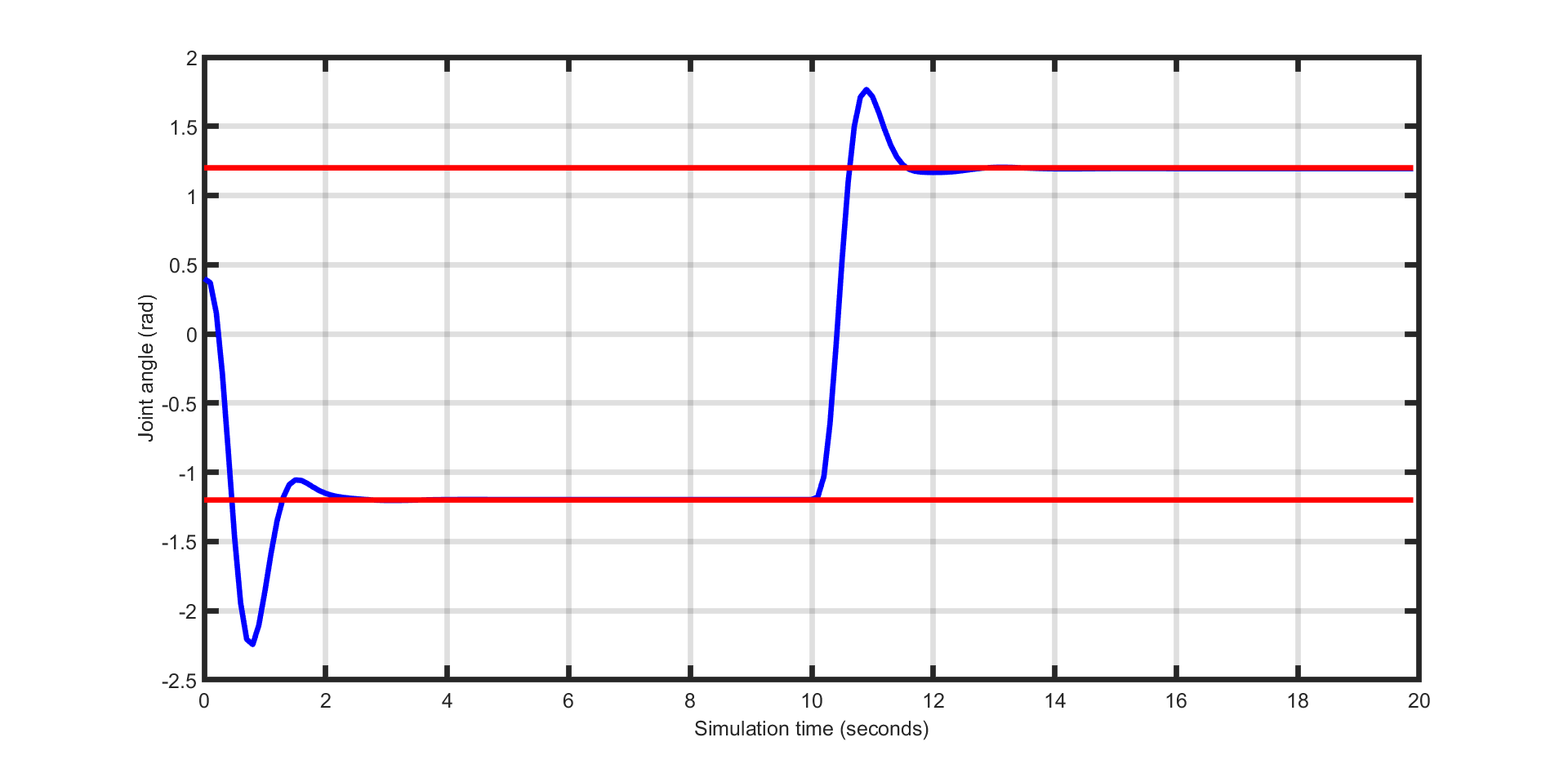

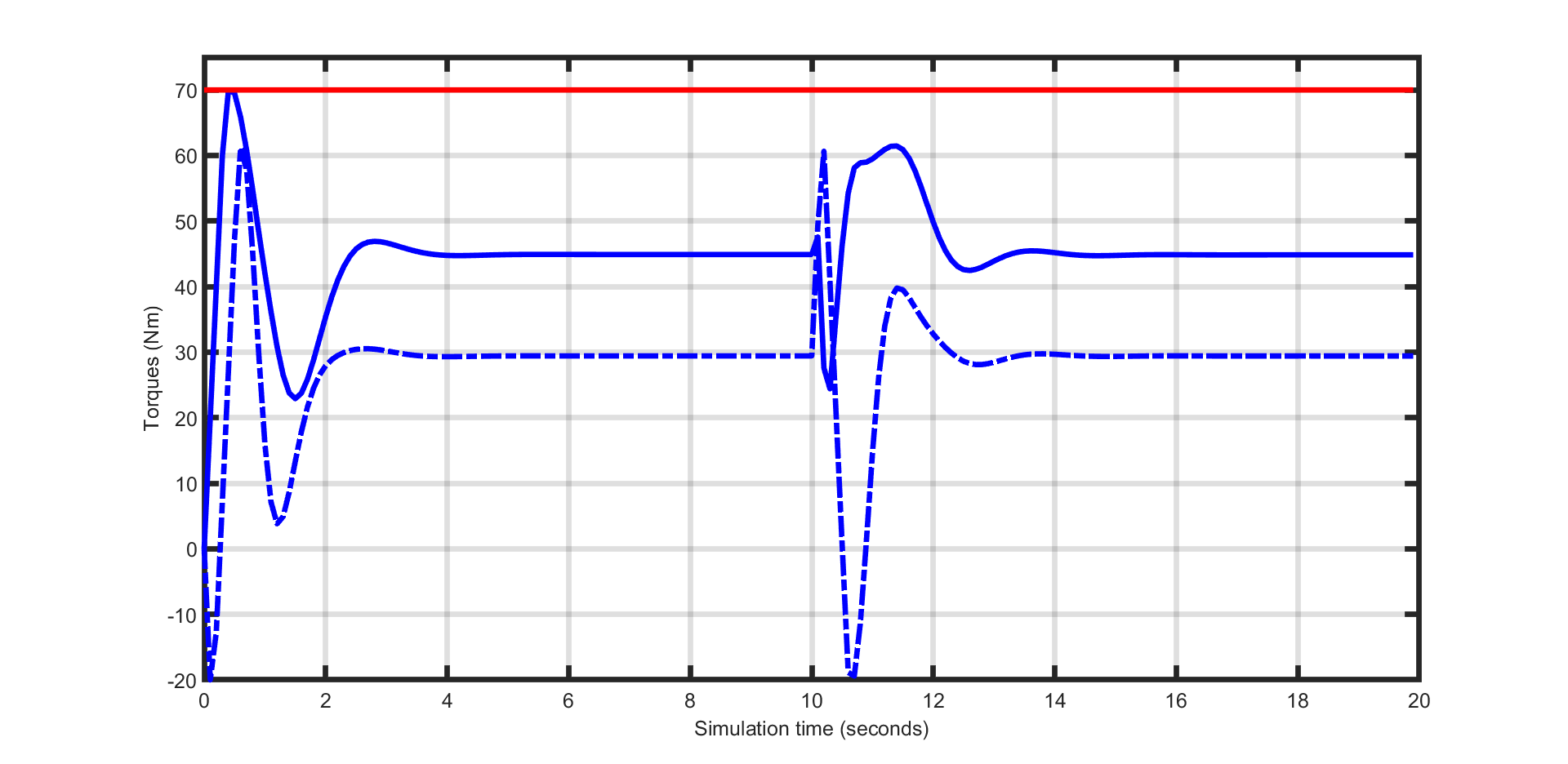

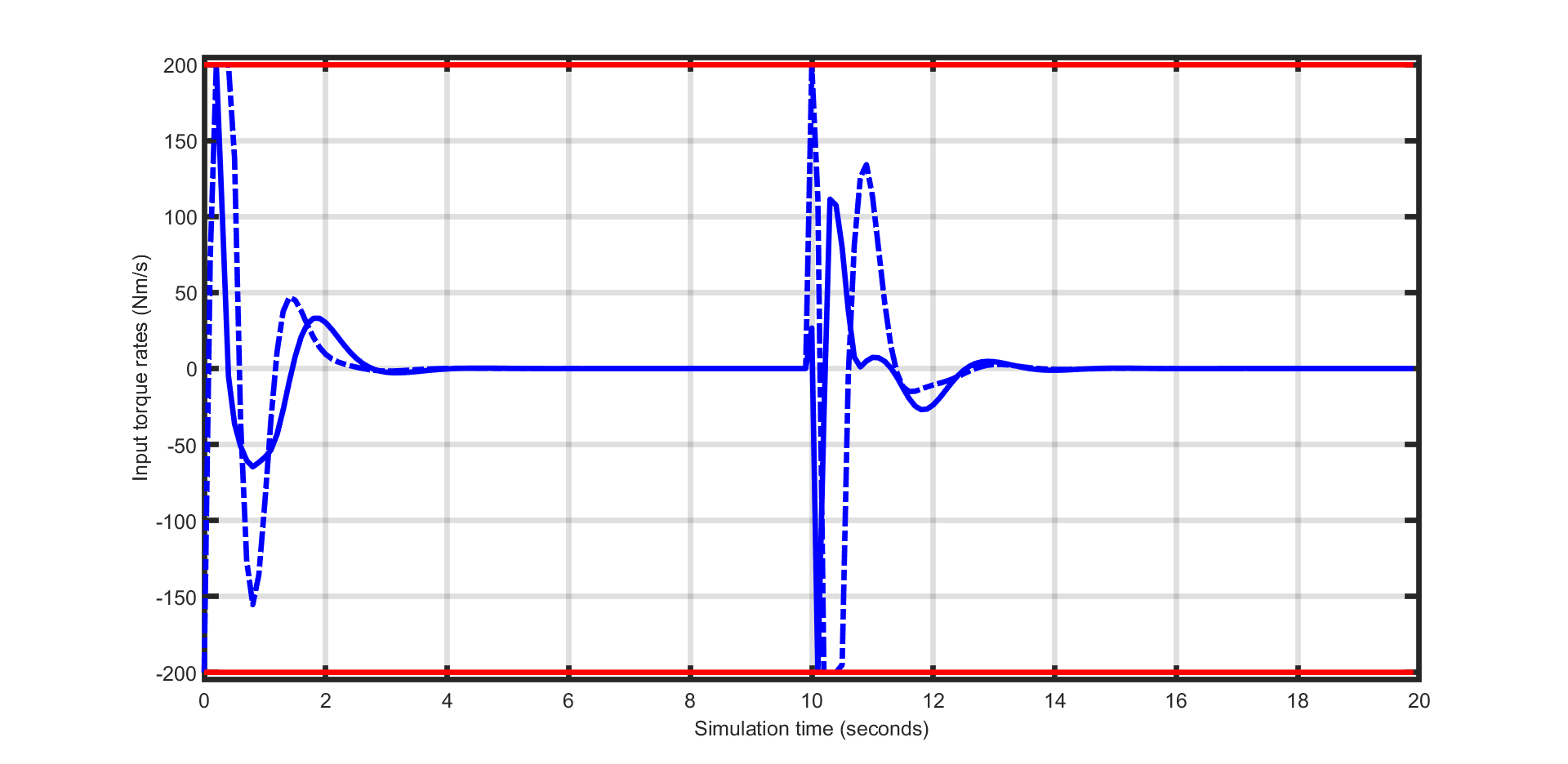

The control objective is to track the joint references of \(-1.2\,\mathrm{rad}\) and \(1.2\,\mathrm{rad}\) respectively, while keeping the input torque rates below \(200\,\mathrm{Nm/s}\) in magnitude and the torque states between \(-100\,\mathrm{N}\) and \(70\,\mathrm{Nm}\).

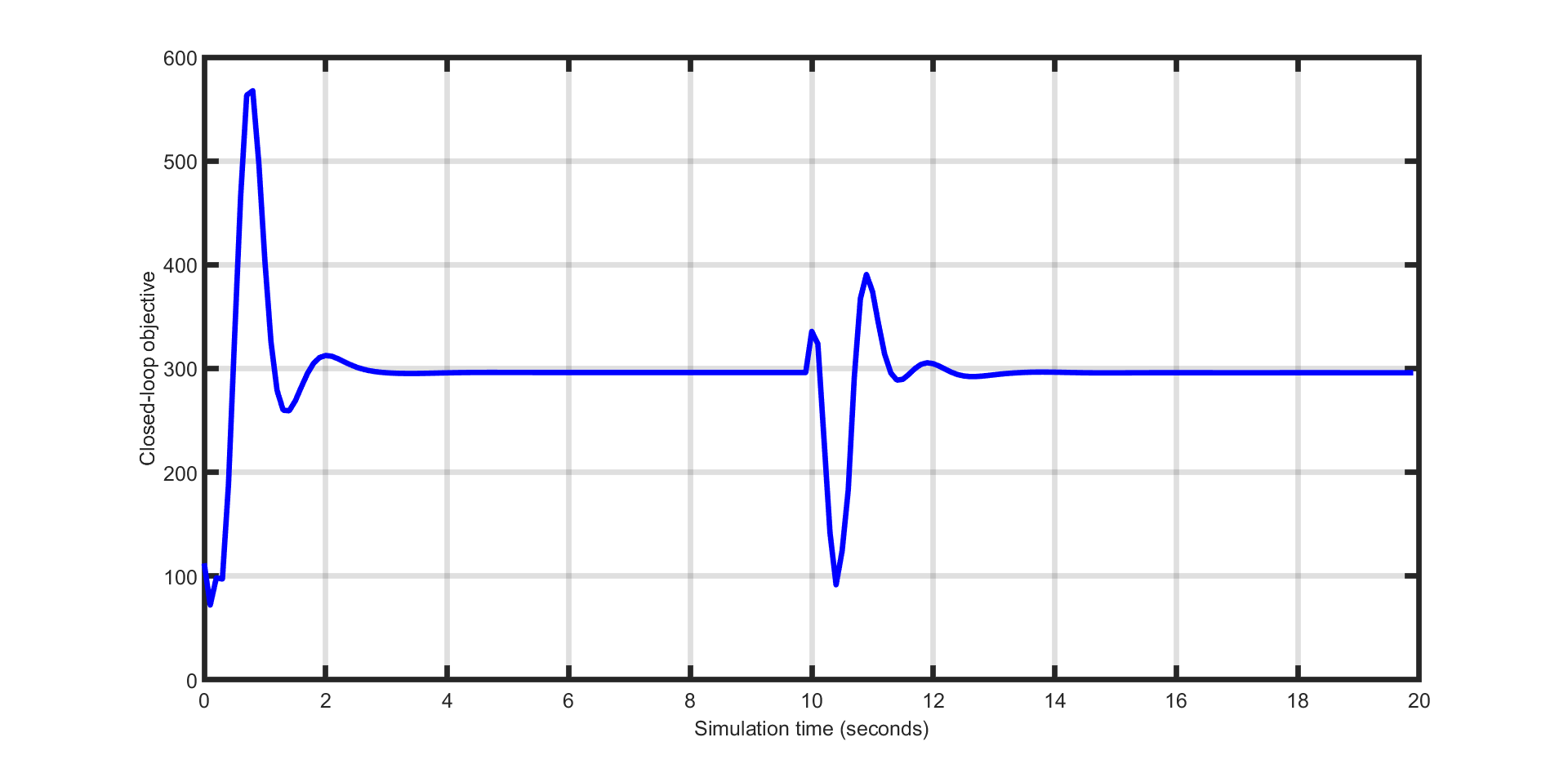

The joint angle and torques trajectories are shown in Figure Figure 11.49 and Figure Figure 11.50 respectively, while the input torque rates are plotted in Figure Figure 11.51. The closed-loop objective, which is a measure of the control performance is shown in Figure Figure 11.52.

Figure 11.49 Manipulator’s joint angle.¶

Figure 11.50 Manipulator’s torques at joints.¶

Figure 11.51 Manipulator’s torque rates.¶

Figure 11.52 Manipulator’s closed loop objective.¶

Siciliano, B.; Sciavicco, L.; Villani, L.; Oriolo, G.. Robotics: Modelling, planning and control. Berlin: Springer, 2009.